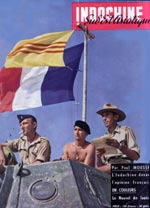

It was June 18th, 1949, in Saigon

A call to arms to commemorate the address by General de Gaulle on June 18th, 1940.

(The June 18th address is the first speech given by General de Gaulle by radio from London on the BBC – it was a call to arms in which he called not to stop combat against Germany and in which he predicted the globalization of the war).

© Photos by Raymond Varoqui, born on July 7th, 1921 in Ottange (Moselle), died February 8th, 2013. He was assigned to the SCA (Army Cinematographic Service) as a photojournalist in 1948. He was immediately sent on a mission with the SPI (Press Information Service) in Indochina.

It was November 11th, 1950, in Saigon

The Monument to the Dead in 1950

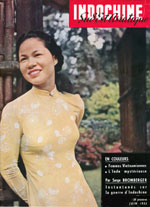

It was April 10th, 1956, in Saigon

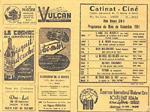

Articles which appeared in the “Journal of the Far-East” of April 11th, 1956

By Jacques Lefebvre

The ultimate farewell from the French Expeditionary Corps to

the soldiers who were killed on the soil of Indochina

The crowd gathered in front of the Eden Cinema at 138 Catinat Street (Eden Mall).

The French Expeditionary Corps in Indochina, represented by five last symbolic detachments courteously accompanied by a Vietnamese company, settled with its dead before leaving Vietnam for good.

This farewell ceremony took place at 1700h, under a grey and stormy sky, in front of the monument at ChiĂŞn-Si Square (formerly Marshal Joffre Square).

This parade under arms, miniscule by its number of participants, had attracted thousands of spectators, not just on the plateau but all the way to the river banks.

We were struck by the kindness – there is no other word – of the Vietnamese public and even more by the often visible sympathy, and more importantly to us, the esteem in which they held our soldiers; these are things one feels.

These weren’t defeated soldiers that these people saw passing by; one doesn’t look at defeated soldiers like that. We inferred from that that certain slander directed at the Expeditionary Corps hadn’t had an effect on the crowd. An attempt had been made to inflate the local disaster of Dien-BiĂŞn-Phu (the result of a strategic error) to the scale of the entire war; they tried to make a gigantic French Điện BiĂŞn Phủ of the eight years of war in Indochina.

As if our soldiers hadn’t half the time “played goalkeeper” in the enemy’s goal!

As if the Vietminh hadn’t copiously bled under the blows of the F.A.E.O.!

The Moroccan Sharpshooters’Band

The Moroccan Sharpshooters’Band passing before the Vietnamese and French officers.

Điện BiĂŞn Phủ is in itself often an admirable page of glory from the standpoint of the combatant. One should re-read the account of Commander Doctor Grauwin, showing us so many wounded who voluntarily went back into combat wrapped up in bandages! And the death of his recent amputees, killed at their gun station with a bloody bandage at the end of their femur!

But the French voters no longer wanted this war which was destroying so many of its sons, and little by little mowed down the entire graduating class of Saint-Cyr (French equivalent of West Point or Sandhurst).

“P.M.F.” (Pierre Mendès-France), a pessimist and realist, knew this very well; he “let it be”: only History will tell if he had chosen the right moment.

It was not in any event our soldiers who were beaten, despite the temporary setback in that cursed valley; it was France which put a stop to it. The Expeditionary Corps didn’t go down for the count. It was the civilian handler who threw in the towel.

The French crownd, collected and vibrant

The Vietnamese crowd, Silent and friendly

A Saigonese crowd from all over.

The Vietnamese people had to have felt all this to crowd around and in front of the men as they passed.

On Catinat Street during the return parade (paradoxically with shades of the departure), we saw a police Jeep at the head of the sharpshooter’s Band, which occasionally with gentleness and good humor, had to play the role of plough in order to make way for the soldiers.

General Pierre Jacquot should be congratulated for the noble idea of this parade, for the composition of the detachments and for the stately and discreet protection of the entire production. The Vietnamese should be thanked for the voluntary participation of their troops – the paratroopers looked splendid - , for the presence of their civilian and military authorities, and for the good-naturedness of their police. As to the French, they were all there, or nearly all, and we need only look within ourselves to know what was going on in their souls.

A personal note as a postscript:

With apologies, we take the liberty of adding a personal word for our readers – dare we say, our friends (?) - to these quick impressions…

An article soaked in melancholy that we planned to dedicate, in yesterday’s newspaper, to the funeral service which was to take place a few hours later, did not get published. Several French friends, whose opinion, in our view, cannot be disputed, strongly suggested we not do so after having asked to read it.

The day before, it was friends of another nationality who had set us straight on a different subject.

This confirmation, coming from all sides, of the impossibility we’re in to freely translate a free thought of a journalist appears to impose upon us, in the constant respect of the rights of the reader, a public demarcation between our professional responsibilities and those sometimes far different that we assume before our conscience and in the thoughts of our friends.

We will henceforth exercise these aforementioned responsibilities in the private sector, outside of the limits of this newspaper.

As for the rest, we will fulfill our responsibility as a journalist and editor in chief under the cover of anonymity, which will spare us a commitment which has become impossible. We will no longer sign any article, but will continue to « arrange » our « copy » with passion ; and if we remove our title of « editor in chief » from the byline, it’s because we refuse of our own accord to masquerade any longer before this opinion of this qualification of imposture. Our duty will continue nonetheless technically with the same conscience, the same devotion to the interests of France and the French people, the same relentlessness...

...We are certain that these minuscule details of the tricks of the trade are of no interest to the reader, who, after all, only expects a lot of news and a little entertainment from newspapers; we therefore apologize straight out for having informed him of this out of an elementary scruple of conscience.

J.L.

The Vietnamese paratroopers and the Sharpshooter’s Band Passing

Duong Tu-Do, which for a short while had become Catinat Street again.

The Vietnamese paratroopers and the Sharpshooter’s Band.

The French Expeditionary Force paraded in the streets of Saigon for the last time on April 10, 1956, in the company of their Vietnamese brothers.

Here they are, marching side by side, shoulder arms, led by the flag.

The funeral on ChiĂŞn-Si Square

After the ceremony, five French detachments and one Vietnamese detachment with flags and banners, paraded before the authorities before crossing the town towards the riverbanks.

Thousands of French and Vietnamese spectators who mingled cordially had gathered in the vicinity of Chiên-Si Square (formerly Marshal Joffre Square) and on the sidewalks of Duy-tân Street, behind the cathedral.

The French patriotic associations, a French delegation from India and numerous civilian and military V.I.P.’s, both French and Vietnamese, had gathered on the mound where the Monument to the Dead is located.

The Monument to the Dead of Saigon

General Pierre-Elie Jacquot is designated Commander in Chief in Indochina by President René Coty. He will hold this position until August 31st, 1956. To his left is Henri Hoppenot, the last French Commissioner-General in Indochina (nicknamed by the soldiers, “Hope Not”).

One especially noticed the presence of most of the members of the Diplomatic Corps, the Prefect of the Saigon-Cholon region, Monsieur Bazé, the councilor of the French Union as well as the French Information Service.

The ceremony began at 16.30h with a salute to the flags and banners. A few minutes later brigadier general Aubert arrived, followed at 16.45h. by vice-admiral Jozan, of the Far-East Maritime Forces, rear-admiral Douget, commander of the Maritime Forces in Indochina, general LĂŞ Van Ty, chief of staff of the Vietnamese Army, accompanied by two other generals, Messrs. Filliol, plenipotentiary minister, assistant high-commissioner, and Hessel, councilor to the embassy.

At 16.55h, General of the Army Jacquot, commander in chief for Indochina, arrived at the foot of the memorial and was saluted by the troops. It would be the same, five minutes later, for the arrival of Ambassador Hoppenot and of Monsieur Trân Trung Dung, assistant secretary of state for national defense, representing the President of the Republic.

As officers and soldiers stood stiffly at attention, the bugle-calls “Aux Champs”(To the Fields), and “Au Drapeau”(To the Flag), rang out, followed by “La Marseillaise” and the Vietnamese national anthem.

French paratroopers presenting arms

French paratroopers presenting arms at the Monument to the Dead.

The minute of silence

General Jacquot at attention before the Monument to the Dead of Saigon.

At 1700h, General Jacquot lays a wreath at the Monument to the Dead. (Other wreaths will be laid a bit later by veterans of the Expeditionary Corps, the French of India….)

Then came the most moving moment: that of the poignant bugle-call “Aux Morts” (To the Dead), and the reverent "Minute of Silence". The crowd then slowly began, with an irresistible movement, to break down the thin barriers; it gathered in its entirety around the mound, in communion with the memory of all those, French, Vietnamese, and of the French Union, who died on the Field of Honor.

The "Marseillaise" and the Vietnamese national anthem brought to a close this homage by the Expeditionary Corps to the lost soldiers.

General Jacquot and two gendarmes (police officers) lay a wreath at the Monument to the Dead of Saigon.

General Jacquot kissing the Vietnamese flag.

The military parade

Then the authorities simply walked to the corner of the former Marc-Pourpe Street, where they would watch the parade of troops preparing to leave the Monument to the Dead and to go down Duy-Tân Street.

At the base of the memorial the bugles ring out, the Drum-Major throws his baton, and the small, but glorious troop moves out.

First the sharpshooter’s band, white-gloved, with green and gold ornamentation; then the flags and banners – including the Vietnamese one – with their honor guard; then the Vietnamese paratroopers in battle dress.

A small group of French National Police, wearing kepis, came next, followed by the French "Paras", and then the Sharpshooters. Sailors and airmen brought up the rear. Such a small parade behind so many flags had never been seen!

French paratroopers on Catinat Street

French paratroopers in front of number 69, Catinat Street.

Through the city

They pass in but a few moments; the authorities get back in their cars. The detachments then follow the resounding band through the traffic circle of the former Norodom Boulevard – packed with people as if a crowded ship -then the cathedral, and head for Catinat Street, mute, petrified, and overflowing with crowds.

The "Chant du DĂ©part" (Departure Song) rings out full-blast.

The parade would continue like this, frequently applauded, along the Argonne Embankment to the Lagrandière Barracks where they would disperse.

The departure of the aviators of the last French military contingent of Saigon in front of the Hotel Majestic located at number 1, Catinat St.

Sincere thanks to Gérard O’Connell

Radio Swallow

The broadcasts of "Radio Swallow", "The Voice of French Forces in the Far-East", will cease transmitting on 11 April 1956 at midnight and the silence which took over their frequency definitively marked the effective departure of the Expeditionary Corps.

This is the text of the speech given by General Jacquot, commander in chief, at the occasion of the cessation of transmission of "Radio Swallow":

"Radio Swallow" will cease broadcasting on the evening of 11 April. The different crews who successively staffed the station for the past five years can be proud of a well-accomplished mission. In a few weeks “Radio Swallow” will be reborn on the soil of Africa and the last contingent of the Expeditionary Corps hearing me tonight will no doubt be among its listeners.

The destiny of the armies of the old military nations is indeed not to know rest. Other delicate missions will be added to those ending in Vietnam. The Government of the Republic recognizes your courage and knows of your experience. I am certain that you will not disappoint the hopes the Nation places in you.

It is in telling you of my confidence in your resolve and my faith in the destinies of the homeland that I wish you good luck, as the station which sustained the morale of the Expeditionary Corps so long and so well goes silent.

The USS Saint-Paul (CA 73)

The French make way for the Americans and in the indifference of the general population, they leave Indochina, nearly a century after their arrival.

Already in 1955, American ships ply the Saigon River. In this photo, the USS Saint Paul (commissioned on September 16th, 1944 in Baltimore) in front of the Hotel Majestic and Tu Do Street (formerly Catinat).

The ship’s godmother was Mrs. John J. Mc Donough, wife of the mayor of Saint Paul, Minnesota.

The USS Saint Paul saw action in China, Korea, and Vietnam, and was decommissioned on April 30th, 1971.

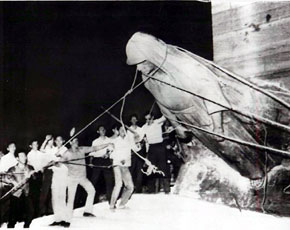

It was July 29th, 1964, in Saigon

French "soldiers" toppled in Vietnam.

Two 30-foot bronze statues of French "Poilus" - World War infanterymen start to topple as Vietnamese students in Saigon pull on ropes attached to figures at French War Memorial last night. The students toppled these statues and another of "Peace" at the memorial is an anti-French demonstration.

Later a crowd of angry French men and women gathered at the remains of the memorial and attempted to fight every Vietnamese that passed.

Police managed to disperse the crowd before any fighting actually began.

© Associated Press 1964